Mastering Tough Multiplets

Alright, time for a little confession. I have been a chemist for nearly 40 years, and used NMR spectroscopy extensively that entire time. Somehow I have never come across the method I am about to discuss, though it has been known since the early 1990’s. Perhaps that’s because the compounds I encountered did not have peaks requiring this approach. Perhaps it is because I could figure out the structures easily enough without worrying about “nasty” multiplet details. Perhaps it is because so often we are confirming an expected structure rather than working with a complete unknown.

I’m talking about those multiplets we encounter that have some decent, symmetrical structure to them, but are too hard to work out exactly what is going on. Those “it almost looks like a quartet of doublets but not quite” peaks. Those “it should be a doublet of triplets but there are not enough peaks” cases.

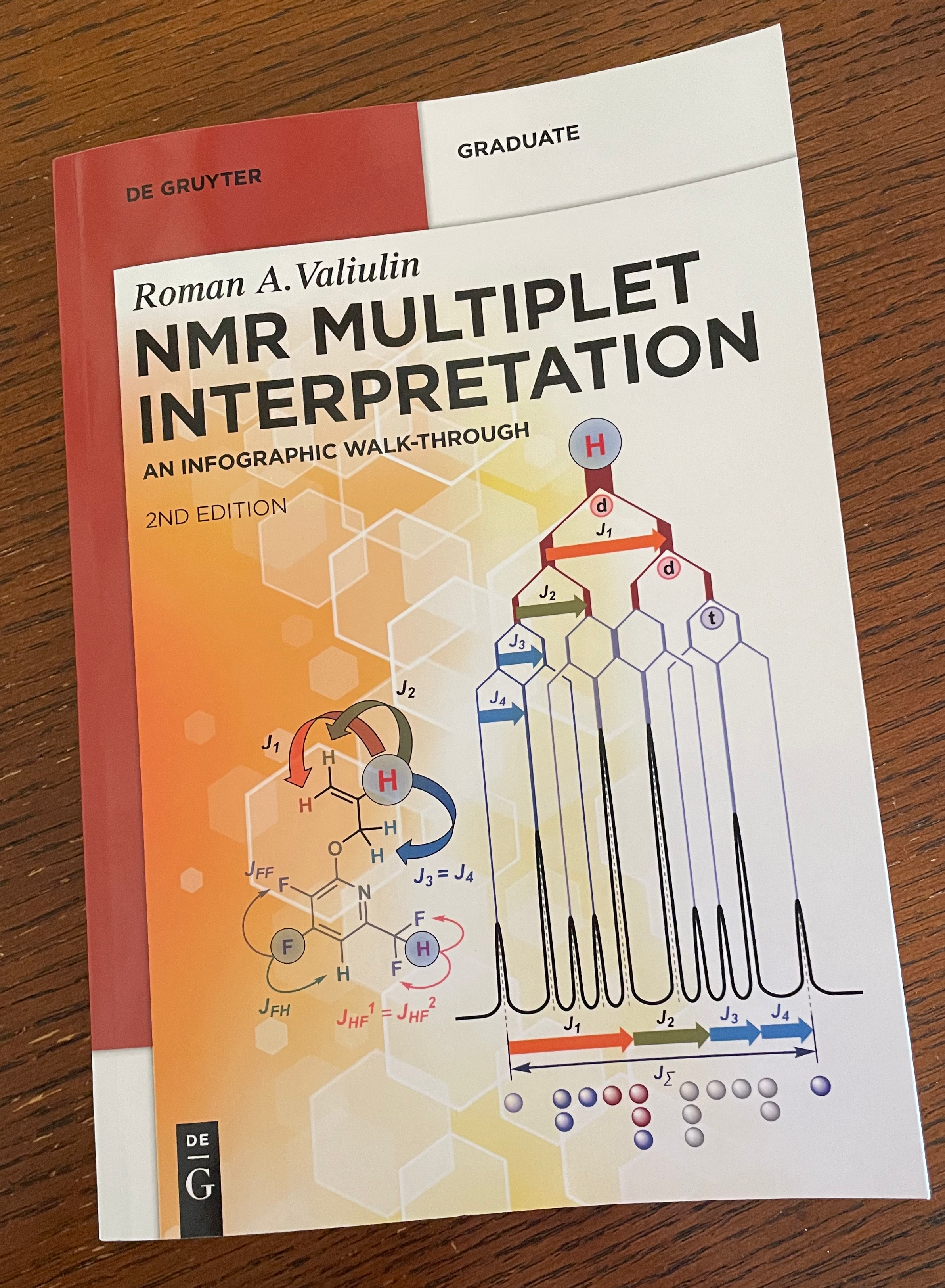

The other day I saw an announcement about a 2nd edition of a book by the visually adept Roman A. Valiulin called NMR Multiplet Interpretation. With a catnip-title like that I ordered it immediately. I have not been disappointed. It’s taught me to look at those multiplet beasts completely differently.

This book teaches an interesting method, originated by Hoye’s lab at Minnesota, that allows one to work out the values of the coupling constants in a complex, first order multiplet without thinking about structure at all.1 Once you have these values, one can determine which type of multiplet is at hand. For instance, is it a doublet of triplets (dt) or a triplet of doublets (td)? Sure, if all the coupling constants are different and the resolution of the instrument is good enough, one can do this by inspection. But if the coupling constants are degenerate or almost so, or we are working with quartets and quintets, then one can end up with a rather complex pattern whose origin is not at all clear, which is when this method shines. With this information, one can then turn back to issues of structure.

I am thinking of this as a “coupling constant forward”2 method, a way to work out those multiplets that in the past one might have been tempted to set aside as too complex to deal with.

This is clearly not a beginner topic in NMR. When we teach NMR to novices, we focus on using the three big pieces of information: chemical shift, area, and splitting, but of course the splitting is almost always very simple. Sometimes students get a taste of the real world when a sample has a doublet of doublets but the two central peaks come close to overlapping; they can often appreciate that with small changes in coupling constants this might look like a triplet. But at the beginning we may not even really talk much about coupling constants, and instead just talk about peak spacing and symmetry.

One interesting aspect of Valiulin’s presentation is he makes very clear how every multiplet is a “doublet of doublets of … of doublets” in this approach. In a J-tree diagram every splitting is a doublet until you’ve got all the coupling constants and have determined that some of them are the same, leading to overlaps in the final pattern of peaks. Using the example from the previous paragraph, a doublet of doublets becomes a triplet once the two coupling constants are the same. This sort of collapsing of peaks is surely appreciated by anyone beyond the novice level, but Valiulin provides some nice demonstrations of how this works when many more spins are involved.

Any of you multiplet junkies (or more so, multiplet avoiders) that haven’t seen this book should definitely get a hold of it.

Footnotes

Reuse

Citation

@online{hanson2025,

author = {Hanson, Bryan},

title = {Mastering {Tough} {Multiplets}},

date = {2025-02-06},

url = {http://chemospec.org/posts/2025-02-06-Multiplets/Multiplets.html},

langid = {en}

}